200. Psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff Exposes the Antidepressant Lies & Chemical Imbalance Myth

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (00:01.922)

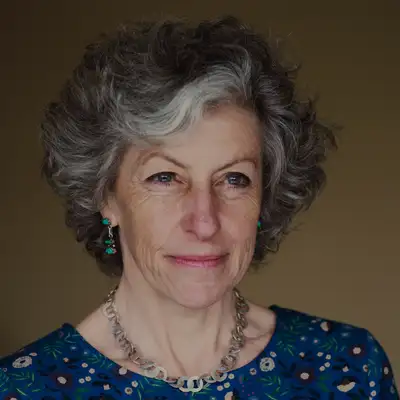

Welcome to the Radically Genuine Podcast. I'm Dr. Roger McFillin. It is an absolute honor today to welcome Professor Joanna Moncrief, who I would argue is the world's foremost scholar, researcher and clinician on the critical examination of psychiatric drugs and the myths surrounding them. She holds the position of Professor of Critical and Social Psychiatry at University College London, where she spent over two decades as both a practicing NHS consultant psychiatrist

and a pioneering researcher. She co-founded and chairs the Critical Psychiatry Network, an international group of psychiatrists with the courage to challenge their own field's foundational assumptions. Professor Moncrief's 2022 paper in molecular psychiatry didn't just make waves, it created a tsunami. Leading a systemic review of five decades of research, she and her team definitively demonstrated that

What no one had dared to state so clearly that there's no convincing evidence that depression is caused by a serotonin imbalance or any chemical imbalance at all. This paper became one of the most widely read scientific papers in modern history, ranking in the top 5 % of all research ever tracked. The world took notice because the world needed to know. Her groundbreaking book, Chemically Imbalanced,

the making and unmaking of the serotonin myth, meticulously documents how an entire medical narrative was constructed without scientific foundation marketed to billions and defended by institutions that should know better. I think what distinguishes Professor Moncrief as the leading authority in this field is her very unique position. She's simultaneously an insider and a reformer.

A senior psychiatrist who treats patients daily in the NHS, who prescribes medication when it may be appropriate, yet has spent 30 years courageously documenting the chasm between what the science actually shows and what the public has been told. No one else combines her clinical experience, research rigor, and unflinching commitment to truth in psychiatric medicine.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (02:26.112)

It's my position that when the history of 21st century psychiatry is written, Professor Moncrief will be remembered as a scholar who had the courage to say that the emperor has no clothes and the scientific credentials to prove it. If you listen to Dr. Moncrief, she has almost a maternal way of being able to explain very complex issues in a way that is caring and respectful of everyone who may be suffering.

I had the honor of being on the same panel with her recently, the FDA's panel for FDA examining SSRIs for pregnant women. And I left again with the utmost respect for her ability to articulate complex issues with compassion. Professor Moncrief, it's truly an honor to have this conversation with you. Welcome to the Radically Genuine Podcast.

Joanna Moncrieff (03:23.908)

Thank you, Roger, and thank you for that amazing introduction. I'm very flattered.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (03:29.494)

Of Before we jump into some of your work, I am just curious on a personal and professional level, when you started to really realize that there were many widespread medical myths that were supporting your profession and how that internal process was for you and how you decided to eventually kind of speak out.

Joanna Moncrieff (03:55.714)

So I mean, I realised quite young, I was reading people like Thomas Saz and R.D. Lang, the anti-psychiatrist or critics of psychiatry at medical school. So by the time I started doing psychiatry, I was already questioning the nature of the area and whether it was sensible to consider this as an area of medicine. But my

Critique of drugs, think, started a bit later because that was really after I started working, you know, working as a junior psychiatrist and seeing people with psychosis and depression and how people responded or didn't respond to the drugs that they were being given.

Joanna Moncrieff (04:46.749)

I wanted to make a comment on something you said in the introduction, I think is important.

So, as I say, from quite an early stage, I felt that the idea that mental health problems and medical conditions is, first of all, not founded in evidence, and secondly, not philosophically sensible or logical either. But that doesn't mean that...

people with these problems don't need help of some sort. And sometimes I think in some situations, I think some drugs can be useful for people on a as temporary a basis as possible. So that's my position. I do question the medical foundation of psychiatry, but I also feel that there are

many situations that involve mental health problems where people do need help and support and where intervention is appropriate.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (05:51.789)

Yeah, to follow up on a comment, you know, one of the things that I think distinguishes historically kind of philosophy or some foundations of psychology versus psychiatry as a medical profession is acknowledgement of the darkness that exists in life. Maybe the acknowledgement of us being a soul.

a soul that is inhabiting a human body for reasons that may be of much greater spiritual importance and including in that darkness is a lot of growth and transformation. that within that darkness, we eventually find our light. know, a lot of people that I work with who've been, you know, born into adverse conditions or experienced significant trauma. Some of them are the wisest people.

that I have ever come across a type of wisdom that can only come from kind of facing that level of suffering and pain. And the medical profession in some sense has pathologized that over the past 30 to 35 years as if there is something that is broken within the individual for experiencing that. And I guess I want to get your thoughts on, you know, how your

profession may have shifted from healers to interventionists through pharmaceuticals and a complete shift of the narrative that supported traditionally the work of psychiatry.

Joanna Moncrieff (07:32.398)

Yeah, that's a good question. So I've done quite a bit of historical research looking back at, for example, old journal articles and textbooks by psychiatrists at the beginning of the 20th, that were written at the beginning of the 20th century. And what's really noticeable is how much more

holistic people were at that time, I suppose it would be one way of describing it. So, you know, psychiatrists, there were articles in those journals, for example, considering madness in Shakespeare and what that had to teach us about the nature of madness in, you know, in more modern life. And other articles that

considered aspects of art and literature and how they might illuminate the problems of the mental health problems. And that's all gone as psychiatry has become increasingly medicalised and modelled on, you know, other branches of medicine with this idea that all mental disorders are, you know, physical pathology or something equivalent to physical pathology that's

that's just an aberration and that we need to get rid of. And like you, really, I try to work out why I have always been upset by the idea that by medicalising mental health problems, why that sort of instinctively seems a wrong thing to do to me. So I tried to work that out a few years ago and I wrote some blogs to try and work out my...

sort of philosophy, I suppose. And just like you're saying, what I realised was that by pathologising dark areas of life or inconvenient aspects of human behaviour or extreme experiences, we are somehow, I think, impoverishingly presenting an impoverished picture of what it is to be human.

Joanna Moncrieff (09:46.064)

And Foucault, Michel Foucault writes about this. He writes about how prior to the Enlightenment, there was this recognition that in madness, out of madness could come profound truths, profound insights into the nature of life. And you can see that in Shakespeare, for example, how you have these so-called mad characters who will tell truths that other people can't see.

or and reveal them to you know, the fool in King Lear, for example. And

And so I think it's a real shame that we've lost that understanding of the great variety of human behaviour and experience and how out of some of the darkest, most perplexing, sometimes most challenging states can come insight, sometimes wisdom.

And even when there isn't great wisdom to be have had just an appreciation of the great variety of human beings and human inclinations, which I think is important to recognize.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (11:05.187)

The chemical imbalance kind of narrative, the marketing narrative that was sold to the Western world. I'm wondering if you've seen something similar or observed, you know, shifts in culture over time. And one of those is that we have created a fear of the internal experience that once through stories or, know, through parenting or through messages passed down through generations, know, emotions were viewed as a signal.

a guide, they were representative of things that you potentially had to face in your life, events, transformational opportunities, and there was more of an acceptance of them. But with this chemical imbalance narrative, it appears that most of the clients, people that I'm working with, there is a judgment of their internal experience, a fear of it. So now emotions are no longer signals, but they are symptoms and potentially something's very serious.

which creates a fear in its own self that takes a lot of time for me as a clinician to kind of unpack, unwind and get them to accept that experience again. I'm curious to know if you're observing something similar in culture.

Joanna Moncrieff (12:19.568)

So, when I was doing the research for my book, Chemically Imbalanced, I went to the archive of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in London, and to look at the papers concerning the Defeat Depression campaign, which was their depression awareness campaign that they ran in the early 1990s, which was partly funded by Eli Lilly, the makers of Prozac, with the very obvious objective of trying to create more customers for

its new antidepressant drug. And looking at those papers was really tragic because they contained surveys that had asked people their views about the nature of depression. And back then in the early 1990s, people replied that they thought that depression was caused by unemployment, divorce, loneliness, child abuse.

In other words, they were describing depression as a reaction to, as an understandable reaction to adverse circumstances. And people also said that they didn't think it was sensible to take drugs, to treat emotional problems. And they were worried about, you know, how those drugs might make them dependent and would just numb their minds rather than solving any problems.

And basically, the Defeat Depression campaign set out to change that mindset, to override people's prior understanding of the nature of emotional problems. And as I say, it was tragic to see that, to see that, you know, people that had this very reasonable instinct about the meaning of the meaning of our emotions, how they were understandable reactions, things that...

that could be worked through or was, as you say, signals about things that might need to be changed in their lives and how just blotting them out with drugs was not the best response and how those ideas were basically suppressed by medical and pharmaceutical company campaigns.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (14:39.524)

I'm going to pause right here. There's people making noise right outside my studio here. I'm just going to come right back. We're going to cut this part out.

Joanna Moncrieff (14:46.586)

Don't worry, I'm going to turn off my email so we don't get notifications.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (15:08.176)

Sorry about that.

Joanna Moncrieff (15:09.615)

Nervous.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (15:10.96)

So a follow-up question on that, because we sat on the FDA panel together, and one of the panelists was describing that postpartum depression would be this underlying, almost brain illness that would emerge. And unless you take antidepressants, which almost would, I think the communication was it was this disease, kind of like diabetes that you would treat.

medically, physically, and without taking the drug, this darkness would emerge. And it would then create a danger to the baby. So it was almost communicating that an SSRI is protective because emotions in themselves are dangerous. Stress would be dangerous to developing fetus. And then God forbid, you know, you're

you have postpartum depression and then it would like interfere with your ability to bond. I wanted to get your thoughts on that kind of narrative that was discussed during the hearing.

Joanna Moncrieff (16:21.1)

So I feel that it's a really irresponsible narrative that is being put out by medical institutions and medical leaders that depression is essentially the same as diabetes and that somehow it's medically irresponsible not to treat it aggressively with antidepressants if necessary. Of course, depression is nothing like diabetes.

That's not to say that it's good to be depressed while you're pregnant or having a baby. Of course it's not, but it's not the same sort of thing as diabetes. And it certainly doesn't respond to treatment in the same way that medical treatment in the same way that diabetes does. So, you know, the completely unquestioned assumption in this point of view is that antidepressants are incredibly effective and make people better. We know that.

they're not incredibly effective. They mostly don't make people any better than they would have been anyway without taking them. Now, it's probably not great to be depressed when you have a baby to have postpartum depression, but there are other ways to help people with depression. As I say, antidepressants are barely effective anyway. And antidepressants also, if they...

if they are having any effects, in my view, it's mainly an emotional numbing effect. And that doesn't seem like a good state to be in when you have a small baby to be numbed by drugs that you're taking. Surely that's the time when you need to be most sensitive actually to the emotions and reactions of people around you, particularly obviously the baby.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (18:17.529)

It's interesting because I think I have only recently begun to investigate the complexity of the serotonergic system. And that's through conversations with people in the medical system who do study this biochemist researchers and so forth. In psychiatry, the narrative is somewhat reduced to the fact that it's very simple. Like if we increase the availability of serotonin in the nerve cell, it's going to be correcting something that may be a

biological abnormality, a genetic abnormality, there's positive consequences to it, like an improving mood. But what I'm learning is that the serotonergic system is quite complex. It does in fact, interface with hormones and human experiences such as pair bonding, gut microbiome, it's regulating emotion. It's almost like it's still a degree that it's mysterious.

and that we've reduced it, we've simplified it to something that would help people understand it in a way that will push them to take the drug or something very simple in the way that the physicians communicate it. So maybe you can tell us a little bit about the serotonergic system and why it is something that is manipulated with pharmaceuticals in psychiatry.

Joanna Moncrieff (19:43.684)

Yeah. So the first thing to say is that we know very little about the specific functions or effects of serotonin. What we know best probably is that it is involved in lots and lots of different biological systems within the brain and in other parts of the body, particularly in the gut, as you mentioned. So it's ubiquitous, it's doing lots of things, but we don't quite understand

what specific things are driven by serotonin. And apart from sexual function, which does seem to, well, apart from a number of things, we know it's involved in bleeding in the, the clotting response, we know that, we know that serotonin actually impairs our clotting ability. So if you

are on drugs that increase your serotonin activity, then you're more likely to bleed, for example. People on SSRIs are prone to bleeding, more prone to bleeding than people who aren't taking them. And we also have pretty good evidence that it is involved in sexual functioning, again, in a negative way. In boosting serotonin activity seems to impair sexual functioning.

whether that's by using SSRIs or a range of other drugs that affect the serotonin system in slightly different ways. It's probably involved in sleep and appetite and lots of other unlearning and memory and these things, but we really don't know how and all the research that is trying to pin down exactly how it might affect our cognitive functioning, our emotional functioning.

moods etc. has really not provided it, not shown any consistent findings.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (21:42.8)

And speaking of the serotonergic system, so as a cultural phenomenon, I've found your 2022 paper and its response by popular culture to be absolutely fascinating and awakening. was, it was a moment that kind of supported my awakening to the interconnected role between media, the pharmaceutical company, major medical organizations and government and the coordinated attacks.

upon you in presenting that paper to the public was disturbing as a just a social scientist who cares about people and cares about informed consent. And it was enlightening to know the forces behind the propaganda around around this drug. I'm going to get into some of it. I had specific episodes at that time, especially

kind of defending you against like the Rolling Stone article that came out here, as well as some major academics from American psychiatry, from like Ivy League institutions who kind of attacked your integrity. And I had a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University on a podcast recently where we talked about your paper. Before I get to his criticism,

Maybe you can kind of walk us through what you found when you examined the serotonin research.

Joanna Moncrieff (23:17.936)

Yes, I will do, but just as a quick point on that, the response to our serotonin paper was a little bit similar to what happened after the FDA panel, wasn't it? You know, this sort of closing down of the establishment, you know, showing a united front. No, you can't possibly say that. So, so we published this review of the research on serotonin and depression in 2022. We'd been working on it for a couple of years.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (23:27.035)

Yes.

Joanna Moncrieff (23:47.264)

I had wanted to do it because for a couple of reasons. First of all, I was aware that the majority of the general public thought that the idea that serotonin is involved in depression, that low serotonin causes depression, is not just an idea. They thought it was an established scientific fact. That was really brought home to me when I went to do a lecture at the German department in my university to a range of

very highly educated professors and other academics, and they were absolutely stunned when I said to them, you know, actually, people don't think that this, you know, that the evidence is really supportive of this idea. So that was one of the reasons for doing it. The other reason for doing it was that

you know, over the last couple of decades, quite a few leading psychiatrists have been forced to admit that actually the evidence for the links between serotonin and depression is not very strong. But there was nowhere that you could point to in the literature that confirmed that. So I thought we really need to get all that evidence together and come to a conclusion. that's what we did. We identified the main areas of research modern

areas of modern research on serotonin and depression. These included research on serotonin levels in the blood, example, serotonin levels and levels of the serotonin metabolite in the cerebrospinal fluid. That's the fluid that covers the brain and the nervous system. Serotonin receptors, the serotonin transporter protein,

the gene for the serotonin transporter protein. been a lot of research done on that. And we also looked at these experiments whereby people have tried to show that, have investigated whether artificially lowering brain serotonin using various procedures can induce depression in people who are not currently depressed and don't have a history of depression. So we

Joanna Moncrieff (26:00.96)

looked at all those different main areas of research and basically there was no consistent or convincing evidence in any of those areas that there was any link between serotonin and depression, let alone a causal link. Because of course, you know, when someone's depressed, of course it may, you know, it's going to affect your brain activity and brain chemistry. So it may be that there are, you know, abnormal chemical states that

correlate with being depressed, but don't necessarily cause it. But we couldn't even find any evidence of a correlation, let alone a causal relationship. Of course, there are some studies that show positive results. There were some studies that suggested there might be a link between, for example, serotonin receptors and depression.

But there were also negative studies. when you put all that, you know, it was just inconsistent when you put all the data together, there was no, there was no clear evidence that the positive studies, that the positive evidence was coming out on top. So that's what we found. And as you said, you know, it inspired a lot of interest in the media and from the general public and

and all sorts of different reactions. And in the early days after the paper was published, I was really hopeful and optimistic. It seemed that this message was finally getting out to the general public. They were finally having a chance to hear the truth and also to reevaluate the nature of antidepressants. Because of course, the first question that anyone asked

asked me when I was talking about this paper was, well, what does that mean for antidepressants? And my answer was that it means that, you know, they are not targeting some underlying chemical imbalance or brain abnormality, as you have probably been told or led to believe. And therefore what they're doing is that, you know, the drugs that are disrupting our normal brain chemistry, the normal

Joanna Moncrieff (28:16.696)

disrupting the normal state of the brain. And, but then gradually, as you've suggested, the sort of hatches came down, the establishment got together and, and encountered, you know, basically trying to shut down the debate, trying to

tried to persuade the public that even though there wasn't evidence for serotonin and depression, they should still go on believing that depression was a biological condition because there were all these other theories out there that might show that depression has biological origins, not that anyone, any of them could claim they did show this because they don't. But that was the, you know, I think the objective was to keep people thinking that depression

is a biological condition and therefore is appropriately treated by antidepressants. And that was thoroughly depressing to see that reaction getting into gear and getting going.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (29:26.726)

Yeah, it was very disappointing. It was unfortunate. but it kind of revealed their alignment with the pharmaceutical industry and how much the profession is really justified by a lot of these underlying theories. And I think that's the legitimate challenge that we're facing is that so many physicians at this point in the United States, it's largely primary care doctors, pediatricians. So many physicians are writing.

prescriptions for these drugs that the dissonance created with the idea that they could be potentially harming, or they are harming what amounts to millions, and they did not provide adequate informed consent there because they weren't educated themselves, they weren't informed themselves. I think it's too much to psychologically bear that they have to go in and defend it. And so this is what the skeptic said is that even if the mechanism may be wrong,

these drugs do help people because I see it every day in my practice. People are reporting that they are feeling better and that experience can't be denied. And so you're curious to know, cause you did mention the questionable effectiveness of a antidepressant, especially in comparison to a placebo drug.

How would you describe what the doctors are seeing and the sometimes reported online experiences of some patients that say it saved their life?

Joanna Moncrieff (31:03.076)

Yeah. So the reason that we do placebo controlled randomised trials is because we know that first of all, that depression usually gets better anyway. will people should say people get better from depression anyway. And secondly, giving someone something like a pill that they are led to believe is going to be helpful.

can at least temporarily boost their mood. So we know that those things are operating what you might call the placebo effect. And that's why we need to test antidepressants against placebos. And if you look at the placebo control trials, you see that antidepressants are...

overall in the ones that are published and the ones that we have access to that are not published, a little bit better than a placebo in terms of reducing your depression rating scale scores. Now, there are all sorts of questions about the validity of measuring depression using a rating scale, but let's put them aside for a minute. The difference is minuscule. Out of a 52-point scale, it's two points.

So it's a trivial difference and no estimate of the minimal level of a clinically significant difference includes two points. All those estimates are way above that. All the ways of estimating what difference actually matters suggest that a two point difference is insignificant and actually probably not even noticeable.

So the, and moreover, that small difference is likely in my view to be accounted for by the fact that these studies, although they're meant to be double blind, are not completely double blind because people can often guess whether they're taking the, whether they've got the real drug, the antidepressant, or whether they've got the placebo.

Joanna Moncrieff (33:20.368)

And because they have side effects like a dry mouth or feeling nauseous, or because they just feel a bit different, it may not be a sort of specific side effect, they may just feel like they're taking a drug. And so because some people can guess whether they're getting the real drug or the placebo, that introduces...

what we might call an amplified placebo effect. The people who are getting the drugs are getting an additional placebo effect because they think they've got the real thing. And conversely, the people who getting the placebo get less of a real placebo effect because they think they're getting it, they're not getting the real thing. And

We know that people's expectations about whether they're getting the real drug or not profoundly affect the results of randomized control trials. So, for example, there's a really neat study that was done in the States with university students, think, people who had social anxiety disorder. They were all given S. citalopram and an SSRI drug, but half of them were told they were

getting a placebo, an active placebo. And half of them were told they were getting a real treatment for social anxiety. And the people who were told they got the real treatment did much better than the people who were told they got the placebo. There was a much bigger difference than the two point difference you see between a drug and a placebo in a straightforward randomized controlled trial. And there are other studies that show that effect too.

In my view, the the response that the you know the sort of main establishment response to our paper, which was antidepressants work and it doesn't matter how is untrue on two counts. First of all, the evidence that they work is minimal. And secondly, how they work, I would say is is very important. What they actually do is very important and

Joanna Moncrieff (35:27.032)

as I mentioned earlier, they are active drugs. When I say that they're no different from a placebo in these randomized controlled trials, we're very minimally different. I'm not suggesting that they are inactive. They are not. They are active drugs that do change our brain chemistry and therefore will inevitably change our mental states in more or less subtle ways. And one of the changes that antidepressants particularly seem to induce is this state of emotional numbing.

So people feel people's emotions, both positive and negative emotions are less intense. And obviously you can see how if people are very distressed and their emotions are numbed a bit, they're then going to appear as if they look a bit better when you do a depression rating scale score with them.

I think probably most of their effect is actually the amplified placebo effect, but there may be some added effect from this emotional numbing. Some people may feel that being emotionally numbed is something that might be useful for them, but actually many people find it a really unpleasant effect and don't like it. And I would certainly argue that, although it may be, may for some people be.

useful, you know, on a very short-term basis, taking something that numbs you, you know, for longer periods of time is not going to be useful. It's not going to enable people to work out why they're feeling depressed or anxious and try and do something about it.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (37:03.634)

Yeah, what's interesting to me, a couple of points on what you said, was I throw myself into the scientific literature on emotion regulation, which if I had to say, is my expertise? My expertise as a clinical psychologist is on emotion regulation, distress tolerance. How do people regulate intense emotions, negative mood states in order to be effective in life and in order to move through difficult times. And one of the things that's very clear,

is that the aspects of emotion regulation include the identification, awareness and experience of that emotion and one's willingness to feel it even at maximum intensity. In fact, the ability to experience it at maximum intensity has a positive outcome in what's somewhat paradoxical is that you will eventually experience that

less intensely. the more we try to escape, the more we try to avoid the greater intensity of the emotion that we experience and chronically so. So I always saw it as somewhat anti-human to almost have a war on emotions and to believe and even to communicate to people that feeling less of an emotion means feeling better. That trying to numb it is something that's going to have a long-term positive effect and the messaging has always been

well, this will help you get through a difficult time. And that's kind of a nefarious message because it says, if you don't feel as bad, then somehow that's going to assist in you getting through that episode when it's exactly the opposite. Feeling fully and facing that fully is what is going to decrease the length of that particular episode. And then my second point,

is around the psych neuroimmunology research that I find absolutely fascinating, which is the connection between emotions and immunity. So the suppression of emotions is correlated with all various types of disease risk factors. we're even seeing written up in medical literature, what can be called spontaneous remission. Sometimes they're just called miracles.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (39:23.988)

You know, people who have been experiencing stage four cancer were sent to really go to hospice or live out the end of their lives. And they made peace with people that they have previously been disconnected from forgiveness. They've experienced emotions as they're facing that loss and they've moved those emotions. And then you've seen like cancer tumors dissipate. You see emotional components with cardiovascular disease.

and a range of other health conditions. And I just feel like the entire messaging that we have around emotions has widespread implications on health and wellbeing.

Joanna Moncrieff (40:07.202)

Yeah, really interesting point. don't know the literature on emotions and immunity terribly well, but I'm sure that there is an effect. But also, I would add that psychoactive drugs, as far as we know, generally have a negative impact on the immune system and make people more susceptible to a whole variety of diseases and conditions.

Coming back to your point about emotion regulation, that just made me think about that you can use it. You can also sort of describe this when you think about someone who's becoming socially withdrawn. You know, if you become socially withdrawn, you know, it becomes self-perpetuating, doesn't it? And it gets more and more difficult to, the longer you, you know, the longer you

stay at home and go out of your front door, the more difficult it gets to go out. And when you, and it's only by going out that you, that you can get over what, you know, overcome whatever it is that was prompting you to, to lock yourself up. And then I was also thinking, I often draw a parallel between

Well, I often highlight the essential similarity of psychiatric drugs like antidepressants and other psychoactive drugs that people use for recreational purposes like alcohol or cannabis. I'm not saying that these are exactly the same sorts of drugs. Clearly, they're, you know, they're different chemical substances, but they're the same to the extent that they change the normal state of the brain and therefore change our

mental states in one way or another. and most psychoactive drugs will have some sort of impact on our emotional states. Now, we could, you know, we could be in a, you know, a very bad state of mind, you know, feeling very low and unhappy or stressed and anxious. And we could, you know, go and get drunk every day. And that would probably fairly effectively obliterate those feelings temporarily.

Joanna Moncrieff (42:25.198)

we'd never recommend that someone should do that. And with using antidepressants, because they do have this emotional numbing effect, we are essentially telling people to do that. Obviously, I'm not saying that the emotional numbing with antidepressants is exactly the same as getting plastered after drinking a bottle of whiskey, whatever, but it is subtly changing people's emotions or seems to be for most people.

And as we recognise with when we think about, you know, using alcohol or other recreational drugs to do that, we can see that that generally has harmful consequences and generally it is important for people to learn to tolerate those emotions and work out where they come from and see them as a signal of things that might need to be changed.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (43:23.572)

question, because a talking point, a rebuttal to some of my viewpoints that I've described around SSRIs in particular, is this belief that the more severe the depression, the better the response. So almost saying yes, we're over prescribing SSRIs, but there is a population where this is much needed. And

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (43:50.944)

The severe depression is a biological medical condition that deserves a pharmaceutical response. And it's just clear that like the data is very clear that for the most severe of depressions, antidepressants are more effective. But our talking point where we say there's only a two point difference on a Hamilton depression rating scale, that's when you put the average together. So I tried to investigate that, but I was unable to find any convincing

evidence that a certain population responds better to an SSRI. Am I missing something? Have you seen it to be any different than I have?

Joanna Moncrieff (44:30.848)

No, no, you're not. And that's a really important point, because I think there is this perception that, OK, maybe antidepressants aren't very useful for most people and have been overprescribed. But of course, there is this group of people with severe depression who have a proper biological condition and respond to antidepressants. None of those things is true. There are people who get very severe depression. That's true and can be very unwell.

can become very withdrawn, even have deludes, of psychotic delusions, can sometimes in extreme states stop eating and drinking. But there's no more evidence that they have any underlying biological abnormalities than there is for the general, a more typical group of people with depression.

All these studies of serotonin, for example, none of these studies of serotonin have distinguished people with different types of depression in that way. None of them have isolated a small group with very severe depression that shows up as having abnormal serotonin, whereas other people don't. And that's true for

or the other areas of biological research, none of them have identified a subgroup of people who have a biological process underpinning their depression as opposed to people who don't. And then the evidence that people with more severe depression respond better to antidepressants is also not there. If you take the vast majority of trials that have been done recently over the last few decades,

that would probably generally exclude people with really severe depression. But these studies, some of the analyses suggest that there may be a slight gradient in that people who have more severe symptoms show a slightly larger difference between the drug and placebo than people who have less severe symptoms. But even the people who are showing

Joanna Moncrieff (46:46.116)

the larger difference, it's still a very small difference, up to maybe about four points on the 52 point Hamilton rating scale, as opposed to two points, if you look at the general average. And that's still almost certainly not clinically relevant, and still also almost certainly explained, at least partly by amplified placebo effects. But the evidence on people who were

have the sort of severe what is sometimes called melancholic depression or psychotic depression who, you know, often admitted to hospital. The evidence that we have for those people actually suggests that antidepressants might be even less useful than they are in the randomised controlled trials of people with more standard everyday types of depression. So

studies that were done back in the 60s with people who were in hospital with depression, for example, showed basically no effects of the antidepressants, the standard antidepressants at the time. Those were not SSRIs, by the way, they were the tricyclic antidepressants, but they're often said to be more effective than the SSRIs by people who put across this argument. But actually, they were not found to be useful. What was found to be useful

in that group of people was ECT. And I think it's the case that ECT can temporarily override someone's underlying emotional state by basically inducing a state of temporary brain injury, which then gradually fades, the brain recovers and people sink back into their

depressive state. So I'm not saying that I'm not recommending ECT. I don't agree with ECT. I think there are other ways of supporting people who are severely depressed. You know, you can have a nurse or an attendant helping, you know, putting, making sure that people get fluid, making sure that they're safe, that sort of thing, until they naturally recover, which people do.

Joanna Moncrieff (49:09.668)

So I'm not recommending ECT, but I'm just using it as an example to show that in these trials, ECT did seem to show a temporary effect, whereas antidepressants didn't.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (49:22.144)

Here in the United States, we're seeing a bit of a cultural revolution. Maha, make America healthy again, has recognized the chronic disease epidemic and seeking to understand all root causes to that epidemic. And in the crossfires is psychiatry and the widespread use of psychiatric medications to treat the range of problems that exist. As this movement has emerged, it's

pushed itself into popular culture. And I'm not sure if you recently listened to our friend and colleague, Dr. Yousef Wit-During was on the Tucker Carlson podcast, which is one of the most, if not the most downloaded podcast in the world. So it brought a lot of these issues to light. Did you have a chance to listen to it by any chance?

Joanna Moncrieff (50:14.752)

I haven't, but I know Joseph well and I know I've heard about some of the things that he said on that podcast and you know, fantastic that Tucker Carlson is bearing this point of view, giving voice to critical perspectives on psychiatric treatments like antidepressants. So yeah, I'm really pleased that he went on. I've heard that he said a lot of very sensible things, which I would mostly agree with, I'm sure.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (50:44.086)

Yeah, I'm actually going to ask for a comment on one of the things he said, because I thought he was amazing. think he's very articulate on a lot of the factors. I think he's very aligned with a lot of what you are sharing today's show. But he's a traditionally trained psychiatrist with not a whole lot of clinical experience. So his background, was with FDA, he worked in with the pharmaceutical companies and he started the Taper Clinic.

Joanna Moncrieff (50:47.728)

Well done.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (51:11.2)

he probably for a good hour and a half talked about all the harms of SSRIs, which we'll speak a little to about in a minute, as well as the fraudulent science base that props it up and supports it from publication bias to how the clinical trials can be manipulated to the potential permanent effects of psychiatric drugs, right? SSRIs, especially potentially being implicated in a number of things post SSRIs.

as is right, sexual dysfunction and violence and suicide. But then Tucker asked him a question, which was, would you ever prescribe an antidepressant? And his answer was yes. So after 90 minutes of disclosing all the dangers of this drug and its limited efficacy, he stated that under some conditions,

that he would prescribe the drug. So I'm curious to know if you share a similar viewpoint that under certain conditions you would be open to prescribing the drugs knowing what those risks are.

Joanna Moncrieff (52:21.231)

Well, I do prescribe them sometimes, not because I think they're going to be beneficial, but because I feel that I have to offer people, I work in the public health service in the UK, I feel that I have to offer people the standard treatments that they would be offered by other psychiatrists. I do it after discussing with them my view of the evidence.

as well as what other people might say about the evidence and obviously going through all the various harms. And then I take the view that, you know, if people have been properly informed and still want to use an antidepressant, given that they are, you know, the standard treatment and very widely prescribed, should, you know, I should enable them to do that.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (53:14.999)

Okay. Would you say that is the highest ethical standard and you have to meet that ethical standard that you respect each individual's right to choose if properly informed and that as your professional oath, you don't have necessarily the right to interfere with a person making medical decisions for themselves.

Joanna Moncrieff (53:37.714)

I mean, I think I think I would argue that probably. Well, I would have argued, I'm not sure whether I'm quite such a libertarian anymore, actually, but I would have argued that we should just deregulate all drugs and they should just all be over the over the counter and people should make their own decisions as long as they were properly informed and that we had done away with all pharmaceutical promotion. I'm not sure that I do quite stick to that now, because I think there's I do think there's a

a human tendency sometimes to take risks, you know, out of desperation to take chemicals that are really not good for you. So I think I probably would favor some regulation nowadays. But I think once you've, know, once something is just being so widely prescribed, you've sort of let the cat out of the bag. we are almost in that realm of

people getting things over the counter, because if they don't get them from me, they'll go to another doctor and they'll get them prescribed if that's what people really want to take. And I feel that at least I can have a proper discussion with someone, I can give them the antidepressant that I think is least harmful at the lowest dose, make sure they're reviewed properly and taken off it if it doesn't work.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (54:54.647)

Thank you.

Joanna Moncrieff (54:55.545)

So I'm not sure whether it's the right ethical approach. know, you know, I'm certainly criticised for it by some people on Twitter for acknowledging that I do prescribe these drugs sometimes, even though I don't think they're effective. And, you know, I don't do that because I think prescribing placebos is a good thing. I don't. I think that's, you know, it's unethical to prescribe placebos. But I think we are sort of almost effectively in an over-the-counter situation, really, I suppose. And therefore, what I'm doing is just...

really providing advice.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (55:27.575)

Thank you. Back to the maha question and the emerging trend, at least here in American culture, you know, one thing is very clear to me is that we have been under attack by industry. Our health is under attack. When you provide American people chemicals and pesticides in food that are banned at other places around the world and accepted and we're mass.

producing that for the American public and we see the consequences of it, we start understanding that the mental suffering is also tied to very important health and wellbeing factors that include what we're putting into our bodies, exercise, combating a sedentary lifestyle. And not to mention like,

dependence on screens and other things that seem to be having negative effects on our health, potentially vaccines as well. The psychiatry in some regards, there's movements where the emotional suffering and the psychiatric conditions that are identified in the DSM are now being communicated as metabolic illness. And I wanted to kind of get your thoughts on this, what appears to be somewhat of a complex and nuanced issue.

about the shift in psychiatry to metabolic psychiatry. Pros and cons and what may be your concerns and what do you see are also the potential benefits.

Joanna Moncrieff (57:04.133)

I mean, I just, I think that mainly this is just shifting to another biological model personally. You know, we've moved away from the chemical imbalance in the brain because there's no evidence and now we're looking at the gut microbiome and, what did you say? And metabolic, and metabolic, using a metabolic model. Don't think there's any more evidence that these are, that

that metabolic issues cause emotional problems than there is that serotonin causes emotional problems or brain, know, abnormalities of brain chemicals cause emotional problems, which is not to say that it's not important to have good metabolic health. Of course it is. And of course there are links between your metabolic health and, know, just your general wellbeing. And it's good for people to, you know, have exercise and a good diet.

But I am sceptical of ideas that there are particular metabolic pathways linked to particular mental disorders. We just haven't got the evidence for that. And I think it's another red herring, essentially.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (58:15.97)

Which leads me to another question. I had a fascinating discussion with Chris Masterjohn, who is like a biochemist. He's, think his PhD might be in like nutritional biochemistry. And he had a series on Substack where he was identifying SSRIs as essentially mitochondria poisons that they destroy the mitochondria of the cell and it impacts all energy production. It almost dims the light of

Joanna Moncrieff (58:16.54)

But.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (58:44.716)

the individual, then we discuss in terms of its emotional effects of that, which can be like a dimming down or a blunting of emotional experiences, cognitive processes. In some respects, people feel detached. They don't care the same way about things that they used to be passionate about. It's impacted relationships, marriages.

And, you know, he, just kind of views that as like, that's the, that's the consequence of when you target, a cell in the way that, that, that drug kind of destroys the mitochondria. I guess my question is this is on, on one respects, the metabolic psychiatry world, Dr. Christopher Palmer, for example, speaks to some of these, like the benefits of what SSRIs do to metabolism.

But I'm looking into the science, I'm looking at research, they're doing the best that they can. It almost seems to me that when you start getting people off of polypharmacy and other psychiatric drugs, in time, their health begins to improve. And so does their emotional state. And we may be misunderstanding the intervention. it's my keto.

Genetic diets may be having somewhat of a positive effect. I certainly think it could help people shift their metabolism to fat burning and for people who are overweight or obese, sedentary, maybe that has a positive effect. But how do we not know that the positive effect is just them abandoning the previous approach where they were poisoning their clients with multiple psychiatric drugs and the return to health is a response of removing that poison?

Joanna Moncrieff (01:00:35.634)

Yeah, no, I agree. Most psychiatric drugs, including most antidepressants, mess about with our metabolic function and are bad for it. And, we can see that because people put on weight, they almost all cause weight gain to some to one degree or another, some worse than others, obviously, and have been linked with increased rates of diabetes and heart disease and things like that. So they're not good for us metabolically, I think.

The idea that they are is pie in the sky and I very much doubt there's much evidence to support that. So I agree, you if people get off their psychiatric medication, they're going to be physically healthier and that is likely to benefit them.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (01:01:25.332)

One final topic area. Again, this is emerging trends in the greater mental health field is the use of psychedelics. And I have mixed kind of feelings about it on one respect. I do believe traditionally and in cultures around the world, plant-based medicines have allowed

for an expansion of consciousness, a greater connection to nature and all things and led to, I think, profound shifts. I'm aware of the reports from those who've been suffering with very severe PTSD, especially combat veterans, and how that psychedelic experience has led to some profound understandings about the meaning of life and their role in some atrocities that morally they've had a difficult time coming to.

some understanding of and, and, and coping with. And then I want to kind of balance that by talking about the same concern that maybe we are with here with SSRIs that if you start pushing ketamine, you start pushing psilocybin, that you're essentially kind of communicating the same thing that you can externally take a substance.

And that can alleviate the pain and suffering. And now an entire industry can grow around this and it actually can be misapplied, not as a potential molecule for spiritual growth, but instead of a treatment. And it represents the medicalization and the profiting off the suffering of people by creating products to sell.

Joanna Moncrieff (01:03:16.679)

Yeah, yeah. So if we look at the history of this recent introduction of psychedelics into medicine and psychiatry in particular, we can see exactly these issues that you're highlighting. So it starts off 10, 15 years ago, maybe a bit more, with this idea of psychedelic assisted psychotherapy. So the idea was people had took a psychedelic

in a sort of controlled environment once or twice and then process that experience either at the time or afterwards with a psychotherapist. And the idea was that the psychedelic experience itself would give people insights into their condition or the meaning of life or something like that that would help them to overcome their PTSD or

alcoholism or depression or whatever it was that they've been suffering from. So that's the model. Now, I don't have any sort of fundamental principled problems with that model, except that I think maybe it's a little bit naive. But I accept that people can get important insights through taking drugs. I think that can happen. I often cite

an example I really like in this book by Gary Greenberg called Manufacturing Depression, that's the name of the book and he tells of when he's

He describes himself as being sort of chronically dysthymic, a grumpy old man, and he's in a relationship with a long-term girlfriend, but he's sort of chronically ambivalent about the relationship and about her. And then they both do a tablet of ecstasy when they go and see a concert, and he suddenly has this revelation that actually he really loves her.

Joanna Moncrieff (01:05:18.535)

This is a revelation that stays with him after he comes down, after the drug and use experience. And they get married and live happily ever after and it's a very sweet story. so I think that can happen. I think people can get revelations, learn important things through the use of drugs, not necessarily just psychedelics, for example. Another example I came across that stuck with me is someone I know who was diagnosed with

Parkinson's disease at quite an early age and got put on quite heavy duty dopamine stimulating essentially stimulant type drugs and got into a very strange mental state where she was sort of obsessionally staying up all night doing karaoke and gardening and her husband eventually took her to the doctor saying do something about her. So she came off those drugs, went on to something else and was better.

But she felt that there had been something about that experience that had liberated her. This was the first time in a very long time that she had actually been living for herself and following her own passions and desires and not spending all her time looking after her children and her husband, keeping the house clean. And so she took something from that experience. She was able to live a bit more for herself and relax a bit.

So the point is, I think we can learn something from taking psychoactive drugs, not just psychedelics, but including psychedelics.

But like you say, the problem is that when that gets commercialized, of course, the expensive part of that process is the psychotherapy that helps people to process the experience. And also, it's not a great business model to give someone a drug a couple of, you know, once or twice and then bye bye, it's all done. So the tendency is you drop all the psychotherapy,

Joanna Moncrieff (01:07:25.007)

And you get people on repeat prescriptions of ketamine and that's exactly what's happened in the States with ketamine, isn't it? We've got all these clinics opened up. The psychotherapy is optional if it exists at all and people are encouraged to at least they certainly end up coming back week after week for repeat prescriptions. There was an article in one of our newspapers here quoting someone who

was having regular ketamine and then her ketamine clinic shut down and she was left very feeling very distressed because she felt she had come to feel that she absolutely needed this and she may well also have been in physical withdrawal of course. So that sort of thing is definitely happening. Are you still receiving me Roger because you've frozen?

Joanna Moncrieff (01:08:22.344)

go on talking and...

So we're ending up, although the model started differently as a psychotherapeutic assisted process to try and capitalize on the insights that people might get from taking psychoactive substances, particularly psychedelics, it is tending towards the same sort of model as antidepressants, that is giving people long-term regular doses of a substance.

Joanna Moncrieff (00:03.164)

So I think we can see exactly what you're saying, saying happening when we think about the use of ketamine in the United States. What's happening is people are going to ketamine clinics, ending up on long-term treatment or long-term repeated treatments, very much like the model of, you know, being on long-term antidepressants. Now, the whole, the movement of

reintroducing or introducing psychoactive, sorry, psychedelic drugs into psychiatry and medicine started off probably a couple of decades ago now with this idea of psychedelic assisted psychotherapy. So it started off as the idea that someone would take one or two doses of a psychedelic drug.

be it psilocybin or ecstasy or something like that. And then they would have a psychedelic experience and then they would process that with a psychotherapist to help them work out what they might have learned through that experience. Now, I have no, I think that's maybe, I think it's maybe a little bit naive and over optimistic, but I have no logical problem with that model.

And I do think that people can have positive experiences with psychoactive drugs and can learn things, can have revelations and insights through using psychoactive substances, whether it be psychedelics or other sorts of psychoactive drugs. The problem is that a business model that involves you taking one or two doses of something

and having a lot of psychotherapy and then going away, hopefully cured, is not a good business model. The psychotherapy is expensive and you don't want a customer who just turns up for a few weeks. You want someone who is there with you for years. So the business model that we are seeing emerging as in the ketamine clinics is dropping the psychotherapy and encouraging people to...

Joanna Moncrieff (02:22.694)

come back on an ongoing basis for repeated treatments. So there was a piece in a recent UK newspaper about some ketamine clinics closing down in the States and they interviewed someone who took regular ketamine and was really distressed because her local clinic had closed down and she felt she really needed the ketamine to stay well and she might well

have become physically dependent on it and have been in withdrawal as well. So you can see that although the original idea of this psychedelic assisted psychotherapy may have had some merit to it, although as I say, I think a little naive probably, that it's actually just tending to become very similar to the long-term antidepressant treatment model. This is exemplified by

Esketamine, the drug that's been produced by Janssen, which is essentially the same as ketamine, but it's a powder that you, not a powder, a liquid that you essentially snort. And it's been recommended to be taken twice a week for eight weeks, just like an antidepressant, and then with ongoing treatment for relapse prevention. And just like the antidepressants,

The short-term studies show very little benefit. Almost certainly the benefit that there is is a placebo effect. And there is very little data on the safety of taking this on a long-term basis. And yet we know, at least we know, know because the recreational drug scene that taking long-term ketamine can result in bladder problems, in heart problems, in, you know,

people having accidents because they're dissociated and in depression and suicidal behaviour.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (04:23.478)

It sounds like what you're saying is that the model from the industry perspective is to create repeat customers, which there is a benefit to keeping people sick and dependent.

Joanna Moncrieff (04:39.976)

Yeah, absolutely. all these new drugs are marketed as being non-dependence inducing in comparison to the previous generation of drugs. So when the SSRIs came along, they were said to be, know, they're not addictive. Don't worry about them. People can get off them easily in comparison to the benzodiazepines, which had previously thought to be non-addictive, but then shown to have caused significant withdrawal problems.

And, you know, it's now perfectly clear that antidepressants make people physically dependent and can give people really nasty withdrawal symptoms, which in some cases can go on for months and years after people have stopped taking the drug.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (05:26.594)

I could talk to you for hours, but I want to be respectful of your time. So one final question, and I think it's an important one. I'm curious to know about what you believe the future of psychiatry is as a viable healthcare medical profession that serves the public. What do you think shifts need to take place and what could you envision it in 20 years, 30 years where it really does return to its roots and, you know, psychiatrists are healers.

Joanna Moncrieff (05:55.356)

So a couple of points. I think that the vast majority of what we call mental health problems need to be moved completely out of medicine and probably located help for people who have those mental health problems. And as I say, I'm not advocating that we shouldn't help people, but help should be located, I think, primarily in social services so that people can focus on the reasons why.

they are unhappy or stressed or anxious, whether that's debt problems, relationship problems, employment problems, whatever, rather than...

turning up in a doctor's office where there is an implicit medical framework, even if the doctor does their best to try and challenge that. The minute you walk in the door and there's a stethoscope sitting on the table, you are in an environment which screams at you, there's something wrong with your brain, with your physical body. So I think that needs to be done. Now, there are some people who get into a really

severely disordered mental state. Sometimes we call that psychosis or mania, psychotic depression. There are all these diagnostic labels that we can apply to these extreme states. those people, some of those people at least, will need looking after, keeping safe. And sometimes they need to be, the community needs to be kept safe from them when they're in a really

a really bad state. And someone needs to do that job. And that job sometimes involves giving people psychiatric medication. You I think that when people are acutely psychotic, antipsychotics can be useful for some people. They don't target the psychosis, they don't cure anything, but they can numb people, sedate people.

Joanna Moncrieff (07:57.341)

make people less preoccupied with all the psychotic stuff that's going on in their brain. So those are the things that need to be done. We need to be helping the vast majority of people in social services to deal with the problems in their lives that are leading them to struggle. And we need to help people with more extreme mental states by keeping them safe and secure and sometimes intervening with drug treatments.

that may calm them down and help reduce the intensity of their experiences and the extremity of their behaviour. Now, who does that is, I think, an open question. And whether the people that are doing that need the sort of training that psychiatrists currently have is another interesting question to debate. I think the people who doing that do certainly need some training in

biology and pharmacology. And if you're going to give people drugs at all, you need to understand what you're doing. And actually, you need to have much, much better knowledge of drugs than we currently have. Currently, psychiatrists knowledge of drugs is woeful. It's terrible because all the research is just focusing on this idea that the drugs are tweaking some underlying problem without paying attention to

all the ways in which these drugs are altering the normal state of the body and the brain and all the effects that that has. So whoever it is who's using these drugs needs to be much better educated about the effects of the drugs than people are currently. Whether you call them psychiatrists or not, I don't know. But that's what I think that needs to be done.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (09:41.742)

Thank you. Tell us about about your book. From what I understand, it's going to be released here in the United States shortly. Where can they get it? Why is it important for the United States public to be able to read, especially the large and growing mental health industry? There are so many therapists. There are so many psychologists that are now just emerging because of the mental health crisis. I know in particular that this book is going to be mandated reading here.

Joanna Moncrieff (09:54.334)

Yeah.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (10:11.087)

at my center and in our training clinic. But if you can just share a little bit about your book and when it will be available.

Joanna Moncrieff (10:17.51)

Yeah, of course. So it's called chemically imbalanced. I didn't bring a copy, I'm afraid, or I'd hold it up, but I haven't got one. So it's called chemically imbalanced, the making and unmaking of the serotonin myth. It's going to be published in the States on the 18th of September. So it will be available on Amazon US from then and other booksellers and book outlets in the United States.

You can find out about it through my website as well. I have a website for Joanne Moncrief.com and you can follow me on X as well, which also shows how you can get it. And it is already available in the US as an ebook as well, I should say. But you think you have to go via the UK Amazon site or a UK site to get it at the moment. So that's coming out. Why should people read it? Well,

You know, I continue to be shocked and depressed by how many people still believe that depression is a biological condition, that there is some sort of abnormality in the brains of people who are depressed, whether it's a serotonin abnormality or some sort of other abnormality that can be corrected by antidepressants. This just simply is not true. This is an idea that's been made up to satisfy the professional

insecure to deal with address the professional insecurities of the psychiatric profession and to fill the coffers of the pharmaceutical industry as well as as having some convenient side effects for politicians. It's not true. It's not supported by scientific evidence and and I've charted that in the book. The idea that antidepressants are helpful is also

highly questionable and I present all the evidence on that so that people can make up their own minds essentially as to whether they think there really is supporting evidence that antidepressants are beneficial. And I also show all the evidence on the emotional numbing effects, the connected effects on sexual functioning, which are really important for people to know about. The recent emerging evidence that antidepressants can cause persistent sexual dysfunction, which obviously is

Joanna Moncrieff (12:35.589)

is a key factor if people are going to make an informed decision about whether they want to take these drugs and I go into dependency problems as well as talking a bit about the response to the paper from the public but also from the medical establishment and thinking about why that response may have occurred.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (12:56.973)

I would add that it's a it's an absolute tragedy what's happening here in the US with the drugs being prescribed without informed consent. They being pushed by therapists who have less than adequate knowledge about what SSRIs are and what they're not and the implications of it. It's almost communicated as if it's a benign drug that only have positive consequences. So I think it's it's an it's a book that's critically important to meet the ethical standard of your profession.

It's a patient right, it's a legal imperative, and anyone who is suggesting someone take SSRIs has the responsibility to provide their patient the significant potential for adverse consequences. And I think this book outlines it very clearly, and it's very evidence-based.

Joanna Moncrieff (13:47.519)

And as well as the adverse consequences, I think it is absolutely crucial that it is explained to people exactly what antidepressants are doing and what they're not doing. that it is explained to people clearly that they are not targeting some underlying chemical imbalance or other biological abnormality that we don't know, you know, that we do not have evidence to support that idea and that they are drugs that alter the normal state of our brain chemistry and our normal physical and mental functioning.

Roger K. McFillin, Psy.D, ABPP (14:18.426)

Great. Professor Joanna Moncrief, it was really a pleasure and honor to be able to sit down with you. You're such a wealth of knowledge and I know it's going to benefit the listeners. I just want to thank you for radically genuine conversation.

Joanna Moncrieff (14:32.842)

Thank you, Roger. It's been such a pleasure. I've really enjoyed meeting you and it's been great fun. Thank you.

Creators and Guests